I knitted scarves, then increased my difficulty by jumping straight to sweaters with the help of an artist friend, Joe. He's the one who actually taught me to knit, or more accurately, reminded me how to knit, since my Aunt had taught me as a child.

That was many years ago. Every so often I decide to learn a new technique, often by taking a class but sometimes just by choosing a challenging pattern.

This year I decided that it was finally time to learn how to crochet. A friend made several attempts to teach me but I could never wrap my brain around it or stick with it.

So, I signed myself upnfor a three-week, beginners' crochet class at A Tangled Skein, a lovely little yarn shop in Hyattsville.

It is amazing how humble you feel when trying something completely new. I was definitely not the best and brightest of the students. I got it in my head before I could make my fingers actually hold the fabric properly.

But a little practice and awkwardness becomes sucesss.

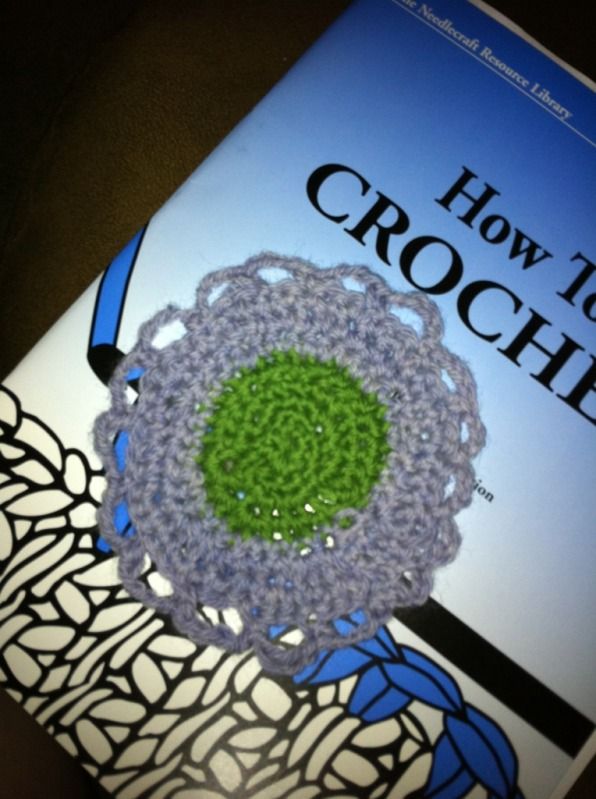

My circular coaster is done! I think I going to like having this new textile skill to draw on. Not bad for a first project.